Drama at the Courts of Queen Henrietta Maria Read Online

| Henrietta Maria | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Anthony van Dyck | |

| Queen consort of England, Scotland and Ireland | |

| Tenure | 13 June 1625 – thirty January 1649 |

| Built-in | (1609-eleven-25)25 Nov 1609 Palais du Louvre, Paris, France |

| Died | 10 September 1669(1669-09-10) (anile 59) Château de Colombes, Colombes, France |

| Burial | xiii September 1669 Royal Basilica of Saint Denis |

| Spouse | Charles I, King of England (k. 1625; died 1649) |

| Effect more... |

|

| House | Bourbon |

| Father | Henry Four, Male monarch of France |

| Mother | Marie de' Medici |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature | |

Henrietta Maria (French: Henriette Marie; 25 November[1] 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland from her wedlock to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until Charles was executed on thirty January 1649. She was mother of his 2 immediate successors, Charles II and James 2 and 7. Contemporaneously, by a decree of her husband, she was known in England equally Queen Mary, but she did non similar this proper name and signed her letters "Henriette R" or "Henriette Marie R" (the "R" standing for regina, Latin for "queen".)[ii]

Henrietta Maria's Roman Catholicism made her unpopular in England,[3] and likewise prohibited her from being crowned in a Church of England service; therefore, she never had a coronation. She immersed herself in national affairs as civil war loomed, and in 1644, following the birth of her youngest daughter, Henrietta, during the superlative of the First English Civil War, was compelled to seek refuge in France. The execution of Charles I in 1649 left her impoverished. She settled in Paris and returned to England after the Restoration of Charles Ii to the throne. In 1665, she moved dorsum to Paris, where she died four years later.

The North American Province of Maryland, a major haven for Roman Cosmic settlers, was named in award of Queen Henrietta Maria. The name was carried over into the current U.S. country of Maryland.

Childhood [edit]

Henrietta Maria as a princess of France

Henrietta Maria was the youngest girl of Henry IV of France (Henry III of Navarre) and his second wife, Marie de' Medici, and was named subsequently her parents. She was born at the Palais du Louvre on 25 Nov 1609, but some historians give her a birth-appointment of 26 November. In England, where the Julian calendar was still in use, her appointment of birth is ofttimes recorded as 16 November. Henrietta Maria was brought up as a Roman Cosmic. As a daughter of the Bourbon king of French republic, she was a Fille de France and a member of the Firm of Bourbon. She was the youngest sister of the future Louis XIII of France. Her begetter was assassinated on xiv May 1610, when she was less than a twelvemonth quondam. As a child, she was raised under the supervision of the imperial governess Françoise de Montglat.

Henrietta Maria was trained, forth with her sisters, in riding, dancing, and singing, and took part in court plays.[4] Although tutored in reading and writing, she was non known for her academic skills;[iv] the princess was heavily influenced by the Carmelites at the French courtroom.[4] Past 1622, Henrietta Maria was living in Paris with a household of some 200 staff, and marriage plans were being discussed.[5]

Marriage negotiations [edit]

Henrietta Maria first met her future husband in 1623 at a court amusement in Paris, on his way to Espana with the Knuckles of Buckingham to discuss a possible marriage with Maria Anna of Spain.[5] The proposal fell through when Philip IV of Spain demanded Charles convert to the Cosmic Church and live in Spain for a twelvemonth, as pre-conditions for the spousal relationship. As Philip was enlightened, such terms were unacceptable, and when Charles returned to England in October, he and Buckingham demanded King James declare war on Spain.[six] Searching elsewhere for a helpmate, in 1624 Charles sent his close friend Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland, to Paris. A Francophile and godson of Henry Iv of French republic, Holland strongly favoured the spousal relationship, the terms of which were negotiated by James Hay, 1st Earl of Carlisle.[vii]

Henrietta Maria was aged fifteen at the fourth dimension of her matrimony, which was not unusual for royal princesses of the period.[4] Opinions on her appearance vary; her niece Sophia of Hanover commented that the "beautiful portraits of Van Dyck had given me such a fine idea of all the ladies of England that I was surprised to see that the queen, who I had seen as so cute and lean, was a woman well past her prime. Her arms were long and lean, her shoulders uneven, and some of her teeth were coming out of her mouth similar tusks....[viii] She did, however, accept pretty eyes, nose, and a expert complexion..."[8]

Queenship [edit]

A proxy wedlock was held at Notre-Dame de Paris on 1 May 1625, where Duke Claude of Chevreuse stood as proxy for Charles, shortly after Charles succeeded every bit male monarch, with the couple spending their first night together at St Augustine'south Abbey near Canterbury on thirteen June 1625.[9] As a Roman Catholic, Henrietta Maria was unable to participate in the Church of England ceremony on two February 1625 when Charles was crowned in Westminster Abbey. A suggestion she exist crowned past Daniel de La Mothe-Houdancourt, the bishop of Mende who accompanied her to England, was unacceptable, although she was allowed to scout her hubby'due south coronation at a unimposing distance.[x] This went down desperately with the London crowds,[11] while England's pro-French policy gave way chop-chop to a policy of supporting French Huguenot uprisings, and then a disengagement from European politics, as internal problems grew.[12]

Afterwards an initially difficult menstruum, she and Charles formed a close partnership and were devoted to each other, but Henrietta Maria never fully assimilated into English society. She did non speak English earlier her marriage, and as late equally the 1640s had difficulty writing or speaking the linguistic communication.[11] Combined with her Catholicism, this made her unpopular among English language contemporaries who feared "Papist" subversion and conspiracies such equally the Gunpowder Plot. Henrietta Maria has been criticised every bit being an "intrinsically apolitical, undereducated and frivolous"[13] effigy during the 1630s; others have suggested that she exercised a degree of personal power through a combination of her piety, her femininity, and her sponsorship of the arts.[14]

Catholicism and household [edit]

A devout Roman Catholic,[17] her organized religion heavily influenced Henrietta Maria's time as queen, peculiarly the early on years of her marriage. In July 1626, she acquired huge controversy past stopping at Tyburn to pray for Catholics executed at that place,[18] and afterwards tried to convert her Calvinist nephew Prince Rupert during his stay in England.[8]

At first, there was uncertainty about the new Queen'south name, and 1 historian has said of this "… Henriette or Henrietta seeming altogether too fanciful for English gustation". Afterwards prayers had been offered for her as "Queen Henry", the king adamant the question past announcing that she was to be known publicly as "Queen Mary". He himself liked to call her "Maria".[xix] In using the proper name of Queen Mary, the English language volition also have been reminded of Charles'south grandmother, Mary, Queen of Scots.[20]

Henrietta Maria was open about her beliefs, obstructing plans to require the eldest sons of Catholic families to be raised as Protestants, and also facilitated Catholic marriages, a crime nether English law at the fourth dimension.[20]

The new queen brought with her a huge quantity of expensive possessions, including jewellery, ornate clothes, x,000 livres worth of plate, chandeliers, pictures and books. She was also accompanied past a large and costly retinue, including her ladies in waiting, twelve Oratorian priests, and her pages.[5] Charles blamed the poor start to his marriage on these advisors, primarily her principal confidante Madame St. George. He ordered their dismissal on 26 June 1626, profoundly upsetting Henrietta Maria, while some refused to exit, including the Bishop of Mendes who cited orders from the French male monarch. In the terminate, they were physically ejected, but she managed to retain her chaplain and confessor, Robert Phillip, along with seven of her French staff.[21]

Their removal was office of a programme to control her improvident expenditure,[5] which resulted in debts that were still being paid off several years later. Charles appointed Jean Caille as her treasurer; he was succeeded by George Carew, then by Sir Richard Wynn in 1629.[22] Despite these reforms and gifts from the king, her spending continued at a high level; in 1627, she was secretly borrowing money,[23] and her accounts show large numbers of expensive dresses purchased during the pre-state of war years.[24]

There were fears over her health, and in July 1627 she travelled with her md Théodore de Mayerne to accept the medicinal jump waters at Wellingborough in Northamptonshire, while Charles visited Castle Ashby Business firm.[25]

Over the next few years, the Queen'south new household began to form around her. Henry Jermyn became her favourite and vice-chamberlain in 1628. The Countess of Denbigh became the Queen'south Head of the Robes and confidante.[26] She acquired several court dwarves, including Jeffrey Hudson[15] and "little Sara".[27] Henrietta Maria established her presence at Somerset House, Greenwich Palace, Oatlands, Nonsuch Palace, Richmond Palace and Holdenby as part of her jointure lands by 1630. She added Wimbledon House in 1639,[5] which was bought for her equally a present past Charles.[28] She likewise acquired a menagerie of dogs, monkeys and caged birds.[16]

Relationship with Charles [edit]

Henrietta Maria and Rex Charles I with Charles, Prince of Wales, and Princess Mary, painted by Anthony van Dyck, 1633. The greyhound symbolises the marital fidelity betwixt Charles and Henrietta Maria.[29]

Henrietta Maria's marriage to Charles did not begin well and his ejection of her French staff did not improve it. Initially their relationship was frigid and argumentative, and Henrietta Maria took an immediate dislike to the Duke of Buckingham, the King'south favourite.[thirty]

1 of Henrietta Maria's closest companions in the early days of her union was Lucy Hay, wife of James Hay who helped negotiate the marriage and who was now a gentleman of the bedchamber to Charles. Lucy was a staunch Protestant, a noted beauty and a strong personality. Many contemporaries believed her to be a mistress to Buckingham, rumours which Henrietta Maria would have been aware of, and information technology has been argued that Lucy was attempting to control the new queen on his behalf.[31] Nevertheless, past the summertime of 1628 the two were extremely close friends, with Hay one of the queen's ladies-in-waiting.[31]

In August 1628, Buckingham was assassinated, leaving a gap at the imperial courtroom. Henrietta Maria's relationship with her husband promptly began to ameliorate and the 2 forged deep bonds of love and amore,[32] marked by diverse jokes played by Henrietta Maria on Charles.[33] Henrietta Maria became pregnant for the first fourth dimension in 1628 but lost her first child soon after birth in 1629, following a very difficult labour.[34] In 1630, the future Charles II was built-in successfully, however, following another complicated childbirth by the noted dr. Theodore de Mayerne.[35] By now, Henrietta Maria had effectively taken over Buckingham's part equally Charles's closest friend and advisor.[36] Despite the ejection of the French staff in 1626, Charles'southward court was heavily influenced past French society; French was usually used in preference to English, beingness considered a more polite language.[11] Additionally, Charles would regularly write messages to Henrietta Maria addressed "Dear Heart." These messages showcase the loving nature of their relationship. For example, on 11 January 1645 Charles wrote, "And dear Heart, thou canst not but be confident that at that place is no danger which I will non hazzard, or pains that I will not undergo, to savor the happiness of thy company"[37]

Henrietta Maria, as her relationship with her husband grew stronger, carve up with Lucy Hay in 1634.[38] The specific reasons are largely unclear although the ii had had their differences before. Hay was an ardent Protestant, for instance, and led a rather more dissolute life than the Queen; Henrietta Maria may besides have felt rather overshadowed by the confident and cute Hay and because she at present had such a close bond with her husband, such confidants were no longer as necessary.[39]

Art patronage [edit]

Henrietta Maria had a strong interest in the arts, and her patronage of various activities was ane of the various ways in which she tried to shape courtroom events.[14] She and Charles were "defended and knowledgeable collectors" of paintings.[28] Henrietta Maria was specially known for her patronage of the Italian painter Orazio Gentileschi, who came to England in 1626 in the entourage of her favourite François de Bassompierre.[twoscore] Orazio and his daughter Artemisia Gentileschi were responsible for the huge ceiling paintings of the Queen'southward House at Greenwich.[41] The Italian Guido Reni was some other favourite artist,[42] forth with the miniature painters Jean Petitot and Jacques Bourdier.[43]

Henrietta Maria became a key patron in Stuart masques, complementing her married man'south potent involvement in paintings and the visual arts.[44] She performed in various works herself, including equally an Amazon in William Davenant'south 1640 "Salmacida Spolia".[14] She was besides a patron of English composer Nicholas Lanier,[45] and was responsible for Davenant being appointed the Poet Laureat in 1638.[46]

The queen liked concrete sculpture and pattern likewise, and retained the designer Inigo Jones every bit her surveyor of works during the 1630s.[five] Like Charles, she was enthusiastic about garden design, although non horticulture itself, and employed André Mollet to create a bizarre garden at Wimbledon Business firm.[47] She patronised Huguenot sculptor Hubert Le Sueur,[43] while her private chapel was apparently on the outside, but its interior included gold and silver reliquaries, paintings, statues, a chapel garden and a magnificent altarpiece by Rubens.[48] It besides had an unusual monstrance, designed by François Dieussart to exhibit the Holy Sacrament.[48]

English language Civil State of war [edit]

During the 1640s, the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland were dominated by a sequence of conflicts termed the English language Civil State of war or the Wars of the Three Kingdoms; within England, the conflict centred on the rival Royalist and Parliamentarian factions. Queen Henrietta Maria became heavily involved in this conflict that resulted in her husband's decease and her exile in French republic. There have been various schools of thought as to Henrietta Maria's office in the civil state of war flow and the degree of her responsibility for the ultimate Royalist defeat.[49] The traditional perspective on the Queen has suggested that she was a strong-willed woman who dominated her weaker-willed husband for the worst; the historian Wedgwood, for case, highlights Henrietta Maria'southward steadily increasing ascendancy over Charles, observing that "he sought her advice on every discipline, except religion" and indeed complained that he could non brand her an official member of his quango.[l] Reinterpretation in the 1970s argued that Henrietta Maria's political role was more than limited, suggesting that the King took more than decisions himself personally.[51] Bone concludes, for example, that despite having a very shut personal human relationship with Henrietta Maria, Charles rarely listened to her on matters of state politics.[52] A third, more recent model argues that Henrietta Maria did indeed exercise political power and influence during the conflict, less so directly but more every bit a result of her public actions and deeds, which constrained and influenced the choices available to Charles.[53]

Pre-war years [edit]

By the end of the 1630s, relations between the English factions had become increasingly tense. Arguments over religion, society, morals, and political power became increasingly evident in the years before war broke out. Henrietta Maria's strong views on religion and social life at the courtroom meant that, by 1642, she had go a "highly unpopular queen who apparently never successfully commanded intense personal respect and loyalty from almost of her subjects".[54]

Henrietta Maria remained sympathetic to her fellow Catholics, and in 1632 began structure of a new Catholic chapel at Somerset House. The old chapel had been securely unpopular among Protestants, and in that location had been much talk amongst London apprentices of pulling it downward equally an anti-Cosmic gesture.[48] Although pocket-size externally, Henrietta Maria'south chapel was much more elaborate inside and was opened in a especially grand ceremony in 1636.[48] This caused keen alarm amongst many in the Protestant community.[48] Henrietta Maria'due south religious activities appear to have focused on bringing a modern, 17th century European form of Catholicism to England.[33] To some extent, information technology worked, with numerous conversions amongst Henrietta Maria'southward circle; historian Kevin Sharpe argues that there may have been up to 300,000 Catholics in England by the late 1630s – they were certainly more than open up in courtroom society.[55] Charles came nether increasing criticism for his failure to act to stalk the menstruum of high-profile conversions.[56] Henrietta Maria fifty-fifty gave a requiem mass in her private chapel for Begetter Richard Blount, S.J. upon his expiry in 1638. She also continued to act in Masque plays throughout the 1630s, which met with criticism from the more Puritan wing of English society.[57] In nearly of these masques she chose roles designed to advance ecumenism, Catholicism and the cult of Ideal love.[57]

The consequence was an increasing intolerance of Henrietta Maria in Protestant English society, gradually shifting towards hatred. In 1630, Alexander Leighton, a Scottish doctor, was flogged, branded and mutilated for criticising Henrietta Maria in a pamphlet, before being imprisoned for life.[58] In the late 1630s, the lawyer William Prynne, popular in Puritan circles, also had his ears cut off for writing that women actresses were notorious whores, a clear insult to Henrietta Maria.[59] London lodge would blame Henrietta Maria for the Irish Rebellion of 1641, believed to be orchestrated by the Jesuits to whom she was linked in the public imagination.[60] Henrietta Maria herself was rarely seen in London, as Charles and she had largely withdrawn from public society during the 1630s, both because of their want for privacy and considering of the cost of court pageants.[61]

By 1641, an brotherhood of Parliamentarians under John Pym had begun to place increasing pressure on Charles, himself embattled afterwards the failure of several wars. The Parliamentary faction achieved the arrest and subsequent execution of the king's advisers, Archbishop William Laud and Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford. Pym then turned his attention to Henrietta Maria as a style of placing farther pressure on Charles. The M Remonstrance, passed past Parliament at the end of 1641, for instance, did not mention the Queen past proper name, but it was clear to all that she was part of the Roman Catholic conspiracy the remonstrance referred to and condemned.[62] Henrietta Maria's confidant Henry Jermyn, who had himself converted to Catholicism in the 1630s, was forced to flee to the Continent afterward the First Army Plot of 1641.

Henrietta Maria encouraged Charles to take a firm line with Pym and his colleagues. She was widely believed to have encouraged Charles to arrest his Parliamentary enemies in January 1642, although no hard proof of this exists.[63] The Marquis de La Ferté-Imbault, the French ambassador, was great to avert any damage to French prestige by an attack on the Queen, but was as unimpressed by Charles's record on relations with France.[64] He advised caution and reconciliation with Pym.[64] The arrest was bungled, and Pym and his colleagues escaped Charles's soldiers, possibly as a effect of a tip-off from Henrietta Maria'southward sometime friend Lucy Hay.[65] With the anti-royalist backlash now in full swing, Henrietta Maria and Charles retreated from Whitehall to Hampton Court.[65]

The situation was steadily moving towards open up war, and in February Henrietta Maria left for The Hague, both for her own safety and to attempt to defuse public tensions almost her Catholicism and her closeness to the male monarch.[66] The Hague was the seat of Henrietta'due south prospective son-in-law, William Two of Orange, and the queen was to accompany the helpmate, her 10-twelvemonth-sometime daughter Mary, to her new home. Too, her widowed sister-in-police force Elizabeth, mother of the queen's old favourite, Prince Rupert, had already been living in The Hague for some years. The Hague was a major centre for banking and finance; the queen intended to raise funds in aid of her husband there.

First English Civil State of war (1642–1646) [edit]

In August 1642, when the Civil War finally began, Henrietta Maria was in Europe at The Hague, raising coin for the Royalist cause. Henrietta Maria focused on raising money on the security of the royal jewels, and on attempting to persuade Prince Frederick Henry of Orange and King Christian Iv of Denmark to support Charles's cause.[67] She was not well during this flow, suffering from toothache, headaches, a cold and coughs.[68] Henrietta Maria's negotiations were hard; the larger pieces of jewellery were both too expensive to exist sold easily, and politically risky – many buyers were deterred in case a future English language Parliament attempted to reclaim them, arguing they had been illegally sold by Henrietta Maria.[69] Henrietta Maria was finally partially successful in her negotiations, especially for the smaller pieces, but she was portrayed in the English printing as selling off the crown jewels to foreigners to buy guns for a religious conflict, adding to her unpopularity at home.[66] She urged Charles, and then in York, to take firm action and secure the strategic port of Hull at the earliest opportunity,[68] angrily responding to his delays in taking action.[70]

At the beginning of 1643, Henrietta Maria attempted to return to England. The kickoff endeavour to cross from The Hague was non an easy 1; battered by storms, her ship came close to sinking and was forced to return to port.[71] Henrietta Maria used the delay to convince the Dutch to release a shipload of arms for the king, which had been held at the asking of Parliament.[72] Defying her astrologers, who predicted disaster, she ready to sea once again at the cease of Feb.[72] This second endeavour was successful and she evaded the Parliamentarian navy to land at Bridlington in Yorkshire with troops and arms.[71] The pursuing naval vessels then bombarded the town, forcing the royal political party to take encompass in neighbouring fields; Henrietta Maria returned under fire, withal, to recover her pet dog Mitte which had been forgotten by her staff.[73]

Henrietta Maria paused for a period at York, where she was entertained in some manner by the Earl of Newcastle.[74] She took the opportunity to discuss the situation north of the border with Royalist Scots, promoting the plans of Montrose and others for an uprising.[75] She also supported the Earl of Antrim's proposals to settle the rebellion in Ireland and bring forces beyond the sea to support the rex in England.[75] Henrietta Maria continued to argue vigorously for nothing less than a total victory over Charles's enemies, countering proposals for a compromise.[76] She rejected private messages from Pym and Hampden asking her to use her influence over the king to create a peace treaty, and was impeached by Parliament shortly afterwards.[77] Meanwhile, Parliament had voted to destroy her private chapel at Somerset House and abort the Capuchin friars who maintained it.[78] In March, Henry Marten and John Clotworthy forced their manner into the chapel with troops and destroyed the altarpiece past Rubens,[78] smashed many of the statues and made a bonfire of the queen's religious canvases, books and vestments.[79]

Travelling south in the summertime, she met Charles at Kineton, near Edgehill, before travelling on to the royal capital in Oxford.[71] The journey through the contested Midlands was not an piece of cake one, and Prince Rupert was sent to Stratford-upon-Avon to escort her.[lxxx] Despite the difficulties of the journey, Henrietta Maria greatly enjoyed herself, eating in the open air with her soldiers and meeting friends along the way.[81] She arrived in Oxford bringing fresh supplies to not bad acclaim; poems were written in her honour, and Jermyn, her chamberlain, was given a peerage by the king at her request.[81]

Merton College chapel, which became Henrietta Maria's individual chapel while she was based in Oxford during the Ceremonious War.[82]

Henrietta Maria spent the autumn and winter of 1643 in Oxford with Charles, where she attempted, as best she could, to maintain the pleasant court life that they had enjoyed earlier the war.[71] The queen lived in the Warden's lodgings in Merton College, adorned with the royal furniture which had been brought upwardly from London.[82] The queen'south usual companions were present: Denbigh, Davenant, her dwarves; her rooms were overrun by dogs, including Mitte.[82] The temper in Oxford was a combination of a fortified city and a royal court, and Henrietta Maria was oft stressed with worry.[83]

By early on 1644, nevertheless, the rex'southward armed services situation had started to deteriorate. Royalist forces in the north came under pressure, and afterward the Royalist defeat at the battle of Alresford in March, the purple uppercase at Oxford was less secure.[84] The queen was significant with Henrietta and the determination was taken for her to withdraw safely west to Bath.[84] Charles travelled equally far equally Abingdon with her earlier returning to Oxford with his sons. It was the last time the two saw each other.[84]

Henrietta Maria eventually continued south-due west beyond Bath to Exeter, where she stopped, awaiting her imminent labour. Meanwhile, withal, the Parliamentarian generals the Earl of Essex and William Waller had produced a program to exploit the situation.[85] Waller would pursue and hold downward the rex and his forces, while Essex would strike s to Exeter with the aim of capturing Henrietta Maria and thereby acquiring a valuable bargaining counter over Charles.[85] By June, Essex'due south forces had reached Exeter. Henrietta Maria had had another hard childbirth, and the king had to personally appeal to their usual physician, de Mayerne, to run a risk leaving London to attend to her.[86] The Queen was in considerable pain and distress,[87] but decided that the threat from Essex was too great; leaving babe Henrietta in Exeter because of the risks of the journey,[88] she stayed at Pendennis Castle, and so took to body of water from Falmouth in a Dutch vessel for French republic on xiv July.[89] Despite coming under fire from a Parliamentarian ship, she instructed her captain to sail on, reaching Brest in French republic and the protection of her French family unit.[90]

By the end of the year, Charles's position was getting weaker and he desperately needed Henrietta Maria to raise additional funds and troops from the continent.[91] The campaigns of 1645 went poorly for the Royalists, notwithstanding, and the capture, and subsequent publishing, of the correspondence between Henrietta Maria and Charles in 1645 following the Boxing of Naseby proved hugely damaging to the royal cause.[92] In ii decisive engagements—the Battle of Naseby in June and the Battle of Langport in July—the Parliamentarians effectively destroyed Charles'due south armies.[93] Finally, in May 1646 Charles sought shelter with a Presbyterian Scottish ground forces at Southwell in Nottinghamshire.[94]

Second and Third English language Civil Wars (1648–51) [edit]

With the support of the French government, Henrietta Maria settled in Paris, appointing as her chancellor, the eccentric Sir Kenelm Digby, and forming a Royalist court in exile at St-Germain-en-Laye.[95] During 1646 there was talk of Prince Charles joining Henrietta Maria in Paris; Henrietta Maria and the King were corking, just the Prince was initially advised non to get, as information technology would portray him as a Catholic friend of France.[96] Afterward the connected failure of the Royalist efforts in England, he finally agreed to join his mother in July 1646.[97]

Henrietta Maria was increasingly depressed and anxious in France,[98] from where she attempted to convince Charles to accept a Presbyterian regime in England as a means of mobilising Scottish back up for the re-invasion of England and the defeat of Parliament. In Dec 1647, she was horrified when Charles rejected the "4 Bills" offered to him by Parliament equally a peace settlement.[99] Charles had secretly signed "The Date" with the Scots, however, promising a Presbyterian government in England with the exception of Charles's own household.[99] The outcome was the Second Civil War, which despite Henrietta Maria'southward efforts to send it some limited military machine aid,[100] ended in 1648 with the defeat of the Scots and Charles'south capture by Parliamentary forces.[100]

In France, meanwhile, a "hothouse" temper had adult amongst the imperial courtroom in exile at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[95] Henrietta Maria had been joined by a wide collection of Royalist exiles, including Henry Wilmot, Lord John Byron, George Digby, Henry Percy, John Colepeper and Charles Gerard. The Queen's courtroom was beset with factionalism, rivalry and dueling; Henrietta Maria had to prevent Prince Rupert from fighting a duel with Digby, arresting them both, however, she was unable to prevent a later on duel between Digby and Percy, and betwixt Rupert and Percy shortly later on that.[101]

King Charles was executed past decree of Parliament in 1649; his death left Henrietta Maria nigh destitute and in shock,[62] a state of affairs non helped by the French civil war of the Fronde, which left Henrietta Maria's nephew Rex Louis XIV short of money himself. During the ensuing, and final, Tertiary English Civil War the whole of the Royalist circle now based itself from St-Germain, with Henrietta Maria'due south followers being joined past the old Royalist circle who had been with her son Charles 2 at the Hague, including Ormonde and Inchiquin and Clarendon, whom she particularly disliked.[102] She besides quarrelled with Ormonde: when she said that if she had been trusted the Rex would be in England, Ormonde, with his usual bluntness, retorted that if she had never been trusted the Rex need never have left England. Co-location began to bring the factions together, only Henrietta Maria'due south influence was waning. In 1654, Charles Two moved his court on to Cologne, eliminating the remaining influence of Henrietta Maria in St-Germain.[103]

Henrietta Maria increasingly focused on her faith and on her children, especially Henrietta (whom she called "Minette"), James, and Henry.[104] Henrietta Maria attempted to convert both James and Henry to Catholicism,[104] her attempts with Henry angering both Royalists in exile and Charles Ii. Henriette, notwithstanding, was brought up a Cosmic.[104] Henrietta Maria had founded a convent at Chaillot in 1651, and she lived in that location for much of the 1650s.[105]

Restoration [edit]

Henrietta Maria painted by Sir Peter Lely after the restoration of her son Charles Ii to the throne.

Henrietta Maria returned to England following the Restoration in October 1660 forth with her girl Henrietta. She did not return to much public acclamation – Samuel Pepys counted only three pocket-size bonfires lit in her honor,[106] and described her as a "very picayune plain erstwhile woman [then aged 50], and goose egg more than in her presence in any respect nor garb than any ordinary woman".[107] She took up residence over again at Somerset House, supported by a generous pension.

Henrietta Maria'due south return was partially prompted by a liaison between her 2d son, James, Knuckles of York, and Anne Hyde, the girl of Edward Hyde, Charles Ii's chief government minister. Anne was pregnant, and James had proposed marrying her.[108] Henrietta Maria was horrified; she still disliked Edward Hyde, did not corroborate of the pregnant Anne, and certainly did not want the courtier'south daughter to marry her son. Yet, Charles Ii agreed and despite her efforts the couple were married.[109]

That same September, Henrietta's 3rd son, Henry Stuart, Duke of Gloucester, died of smallpox in London at age twenty. He had accompanied his blood brother King Charles 2 to England in May and had participated in the King's triumphal progress through London. More death was to follow: on Christmas Eve, Henrietta's elder daughter Mary likewise died of smallpox in London, leaving behind a 10-twelvemonth-sometime son, the futurity William III of England.[110]

In 1661, Henrietta Marie returned to France and bundled for her youngest daughter, Henrietta[111] to ally her first cousin Philippe I, Duke of Orléans, the only brother of Louis Fourteen. This significantly helped English relations with the French.[112]

Afterward her daughter'due south wedding, Henrietta Maria returned to England in 1662 accompanied by her son Charles II and her nephew Prince Rupert.[113] She had intended to remain in England for the residuum of her life, but past 1665 was suffering desperately from bronchitis, which she blamed on the damp British weather.[106] Henrietta Maria travelled dorsum to France the same year, taking residence at the Hôtel de la Bazinière, the present Hôtel de Chimay in Paris. In August 1669, she saw the birth of her granddaughter Anne Marie d'Orléans; Anne Marie was the maternal grandmother of Louis 15 making Henrietta Maria an antecedent of nearly of today's royal families. Soon subsequently, she died at the château de Colombes,[114] near Paris, having taken an excessive quantity of opiates as a painkiller on the advice of Louis 14's doctor, Antoine Vallot.[106] She was buried in the French royal necropolis at the Basilica of St Denis, with her centre being placed in a silver casket and buried at her convent in Chaillot.[115]

Legacy [edit]

During his 1631 Northwest Passage expedition in the ship Henrietta Maria, Captain Thomas James named the north west headland of James Bay where it opens into Hudson Bay for her. The U.s.a. state of Maryland was named in her honour by her hubby, Charles I. George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore submitted a draft charter for the colony with the proper name left bare, suggesting that Charles bestow a name in his own honour. Charles, having already honoured himself and several family members in other colonial names, decided to honour his wife. The specific name given in the charter was "Terra Mariae, anglice, Maryland". The English name was preferred over the Latin due in part to the undesired clan of "Mariae" with the Spanish Jesuit Juan de Mariana.[116]

Numerous recipes ascribed to Henrietta Maria are reproduced in Kenelm Digby's famous cookbook The Cupboard of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie Kt. Opened.[117]

A silk and wool mix textile made in 1660, named in honor of the queen (Henrietta Maria).[118]

Genealogical table [edit]

| Henrietta Maria'due south relationship to the houses of Stuart and Bourbon[119] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Issue [edit]

| Proper noun | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charles James, Duke of Cornwall | thirteen March 1629 | thirteen March 1629 | Stillborn |

| Charles II | 29 May 1630 | 6 February 1685 | Married Catherine of Braganza (1638–1705) in 1662. No legitimate issue. |

| Mary, Princess Royal | 4 November 1631 | 24 December 1660 | Married William Ii, Prince of Orange (1626–1650) in 1641. Had issue. |

| James II & VII | 14 October 1633 | sixteen September 1701 | Married (1) Anne Hyde (1637–1671) in 1659; had issue (two) Mary of Modena (1658–1718) in 1673; had issue |

| Elizabeth | 29 December 1635 | eight September 1650 | Died young; no outcome. Buried Newport, Isle of Wight |

| Anne | 17 March 1637 | 8 December 1640 | Died immature; no issue. Buried Westminster Abbey |

| Catherine | 29 January 1639 | 29 January 1639 | Died less than half an hour afterward baptism;[120] buried Westminster Abbey. |

| Henry, Duke of Gloucester | 8 July 1640 | 18 September 1660 | Died unmarried; no issue. Buried Westminster Abbey |

| Henrietta | 16 June 1644 | 30 June 1670 | Married Philippe of France, Duke of Orléans (1640–1701) in 1661; had issue |

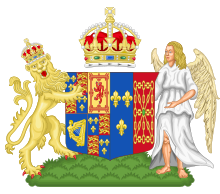

Arms [edit]

Coat of Arms of Henrietta Maria of France as Queen consort of England.[121]

The Purple Coat of Arms of England, Scotland and Ireland impaled with her male parent's artillery as King of France and Navarre. The arms of Henry 4 were: "Azure, three fleurs de lys Or (France); impaling Gules, a cross a saltire and an orle of chains linked at the fess betoken with an amulet vert (Navarre)". For her supporters she used the crowned lion of England on the dexter side, and on the sinister used one of the angels which had for some time accompanied the regal arms of France.[122]

References [edit]

- ^ Burke'southward Peerage and Gentry

- ^ Britland, p. 73.

- ^ Mike Mahoney. "Henrietta Maria of France". Englishmonarchs.co.uk. Retrieved 20 Baronial 2014.

- ^ a b c d Hibbard, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d eastward f Hibbard, p. 117.

- ^ Croft, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Smuts, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Spencer, p. 33.

- ^ Toynbee, pp. 77, 87–8.

- ^ Britland, p. 37.

- ^ a b c White, p. 21.

- ^ Kitson, p. 21.

- ^ Griffey, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Griffey, p. 6.

- ^ a b Raatschan, p. 159.

- ^ a b Purkiss, p. 56.

- ^ Her favourite shrine was the Our Lady of Liesse; Wedgwood 1970, p. 166.

- ^ Purkiss, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Alison Plowden, Henrietta Maria: Charles I's Dogged Queen (2001), p. 28

- ^ a b Purkiss, p. 35.

- ^ White, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Hibbard, p. 119.

- ^ Britland, p. 63.

- ^ Hibbard, p. 133.

- ^ Joseph Browne, Theo. Turquet Mayernii Opera medica: Formulae Annae & Mariae (London, 1703), pp. 112–half dozen

- ^ Hibbard, p. 127.

- ^ Hibbard, p. 131.

- ^ a b Purkiss, p. 57.

- ^ Raatschen, p. 155.

- ^ "Villiers Family". westminster-abbey.org. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ a b Purkiss, p. 63.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 16.

- ^ a b Purkiss, p. 33.

- ^ White, pp. 14–5.

- ^ Spencer, p. 31.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 64.

- ^ Bruce, John. Letters of Male monarch Charles the Beginning to Queen Henrietta Maria. Camden Society, 1856, Pg. 7

- ^ Purkiss, p. 66.

- ^ Purkiss, pp. 64–v.

- ^ Purkiss, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 59.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 60.

- ^ a b Hibbard, p. 126.

- ^ Griffey, p. ii.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 62.

- ^ White, p. xix.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e Purkiss, p. 31.

- ^ White, p. one.

- ^ Wedgwood, 1966, p. 70.

- ^ White, p. 2.

- ^ Bone, p. vi.

- ^ White, p. 5.

- ^ White, p. 20.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 34.

- ^ White, p. 34.

- ^ a b White, p. 28.

- ^ White, 26.

- ^ Purkiss, p. nine.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 113.

- ^ White, p. 22.

- ^ a b Fritze and Robison, p. 228.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 122.

- ^ a b Wedgwood 1970, p. 31.

- ^ a b Purkiss, p. 126.

- ^ a b Purkiss, p. 248.

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, pp. 78–9.

- ^ a b Wedgwood 1970, p. 79.

- ^ White, p. 62.

- ^ White, p. 63.

- ^ a b c d Purkiss, p. 249.

- ^ a b Wedgwood 1970, p. 166.

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, p. 167; Purkiss, p. 250.

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, p. 167.

- ^ a b Wedgwood 1970, p. 199.

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, p. 172.

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, pp. 200–one.

- ^ a b Purkiss, p. 244.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 247

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, p. 215.

- ^ a b Wedgwood 1970, p. 216.

- ^ a b c Purkiss, p. 250.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 251.

- ^ a b c Wedgwood 1970, p. 290.

- ^ a b Wedgwood 1970, p. 304.

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, p. 306.

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, pp. 306–vii.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 324.

- ^ Wedgwood, p. 332.

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, p. 332; Princess Henrietta and her tutor were captured by Parliamentarian forces when Exeter cruel before long afterwards.

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, p. 348.

- ^ White, p. 9.

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, p. 428.

- ^ Wedgwood 1970, pp. 519–520.

- ^ a b Kitson, p. 17.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 404.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 406.

- ^ White, p. 185.

- ^ a b White, p. 186.

- ^ a b White, p. 187.

- ^ Kitson, p. 33.

- ^ Kitson, p. 109.

- ^ Kitson, p. 117.

- ^ a b c White, p. 192.

- ^ Britland, p. 288.

- ^ a b c White, p. 193.

- ^ Diary of Samuel Pepys 22 November 1660

- ^ Kitson, p. 132.

- ^ Kitson, p. 132-3.

- ^ Beatty, Michael A. (2003). The English Imperial Family of America, from Jamestown to the American Revolution. McFarland. ISBN9780786415588. ISBN 0786415584 ISBN 9780786415588

- ^ named after the French Queen Anne of Austria

- ^ Kitson, pp. 134–5.

- ^ Kitson, p. 138.

- ^ The château de Colombes was demolished in 1846; Colombes La Reine Henritte (French).

- ^ White, p. 194.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 42–3.

- ^ Purkiss, p. 352.

- ^ Montgomery, Florence Chiliad. (1984). Textiles in America 1650–1870 : a dictionary based on original documents, prints and paintings, commercial records, American merchants' papers, shopkeepers' advertisements, and pattern books with original swatches of cloth. Internet Archive. New York ; London : Norton. p. 258. ISBN978-0-393-01703-8.

- ^ Fraser 1979, p. five.

- ^ Everett Green, p. 396

- ^ Maclagan, Michael; Louda, Jiří (1999), Lines of Succession: Heraldry of the Purple Families of Europe, London: Little, Brown & Co, p. 27, ISBN1-85605-469-i

- ^ Pinces, John Harvey; Pinces, Rosemary (1974), The Royal Heraldry of England, Heraldry Today, Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press, p. 174, ISBN0-900455-25-X

Bibliography [edit]

- Anselme, Père (1726). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France (in French). Vol. 1 (tertiary ed.). Paris: Compagnie des libraires associez. – House of France

- Britland, Karen. (2006) Drama at the courts of Queen Henrietta Maria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Os, Quinton. (1972) Henrietta Maria: Queen of the Cavaliers. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Croft, Pauline (2003). Male monarch James. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-61395-3.

- Everett Green, Mary Anne. (1855) Lives of the Princesses of England: From the Norman Conquest. Henry Colburn. V. 6

- Fraser, Antonia (1979). King Charles II. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN0-297-77571-5.

- Fritze, Ronald H. and William B. Robison. (eds) (1996) Historical dictionary of Stuart England, 1603–1689. Westport: Greenwood Press.

- Griffey, Erin. (2008) "Introduction" in Griffey (ed) 2008.

- Griffey, Erin. (2008) Henrietta Maria: piety, politics and patronage. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

- Hamilton, Elizabeth (1976). Henrietta Maria. New York: Coward, MacCann & Geoghegan Inc. ISBN9780698107137. OCLC 1149193817.

- Hibbard, Caroline. (2008) "'By Our Management and For Our Use:' The Queen's Patronage of Artists and Artisans seen through her Household Accounts." in Griffey (ed) 2008.

- Kitson, Frank. (1999) Prince Rupert: Admiral and General-at-Sea. London: Constable.

- Maclagan, Michael Maclagan and Jiří Louda. (1999) Lines of Succession: Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe. London: Little, Brown & Co. ISBN 1-85605-469-1.

- Oman, Carola (1936). Henrietta Maria. London: Hodder and Stoughton Express.

- Purkiss, Diane. (2007) The English Civil War: A People's History. London: Harper.

- Raatschan, Gudrun. (2008) "Just Ornamental? Van Dyck'south portraits of Henrietta Maria." in Griffey (ed) 2008.

- Smuts, Malcolm. (2008) "Religion, Politics and Henrietta Maria's Circle, 1625–41" in Griffey (ed) 2008.

- Spencer, Charles. (2007) Prince Rupert: The Final Cavalier. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-297-84610-9

- Stewart, George R. (1967) Names on the Country: A Historical Account of Identify-Naming in the Us, 3rd edition. Houghton Mifflin.

- Strickland, Agnes (1845). Lives of the Queens of England from the Norman Conquest. Vol. viii. London: Henry Colburn. OCLC 861239861. – Henrietta Maria & Catharine of Braganza

- Toynbee, Margaret (1955). "The Wedding Journey of King Charles I". Archaeologia Cantiana. 69. online

- Wedgwood, C. V. (1966) The King's Peace: 1637–1641. London: C. Nicholls.

- Wedgwood, Cicely Veronica (1978) [1st pub. 1958]. The King'southward War 1641–1647 . London: Collins. ISBN0-00-211404-6.

- White, Michelle A. (2006) Henrietta Maria and the English Civil Wars. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

External links [edit]

- A brusk profile of her alongside other influential women of her age

- British Civil Wars Page Biography

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henrietta_Maria

0 Response to "Drama at the Courts of Queen Henrietta Maria Read Online"

Post a Comment